Nature’s cycles proceed inevitably. The sun will set, then rise. The Earth will orbit the sun. The populations of rabbits and lynxes will rise and fall. About once a decade, someone will assert that women are writing fantasy for the very first time in human history.

The latest assertion was penned by a Guardian writer who I am sure can boast of fields in which they are quite well-informed, although apparently none of them involve the long and storied history of women writing fantasy novels. I for one applaud the courage of a person writing outside their field of expertise. One’s reach should always exceed one’s grasp.

Romantasy is, of course, a useful marketing term designed to guide readers to works exhibiting the qualities for which they are looking. The idea is that if people can find the sort of thing for which they are looking, they are more likely to buy it. However, like every other genre, there are works that predate romantasy that would have been classified as romantasy had that term existed.

Consider these five works.

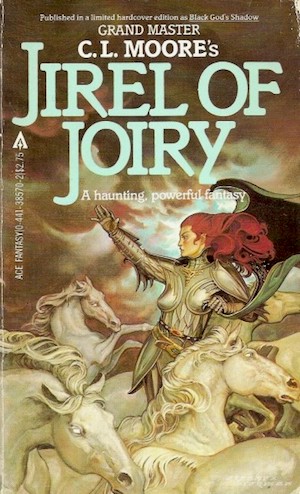

Jirel of Joiry by C. L. Moore (1969)

Jirel is ruler of a small French fiefdom. Overconfident usurpers, evil sorceresses, or besotted gods who mistake Jirel for some fragile flower to be plucked at whim inevitably discover that Jirel protects her prerogatives ruthlessly. Often this is the final discovery her foes make. Should violence fail Jirel—a rare thing—Jirel will resort to even darker measures. And if she sometimes realizes too late that perhaps she was fonder of her foe than she realized before dispatching them? That will not slow her hand when the next vainglorious fool challenges Jirel.

The date above the refers to the collection Jirel of Joiry. The six stories contained within date from the 1930s. Readers seeking more recent work may wish to investigate New Edge Sword & Sorcery, which will feature Molly Tanzer’s authorized Jirel Joiry story, the first new Jirel story in almost eighty-five years.

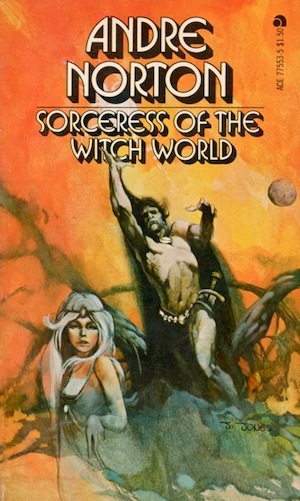

Sorceress of the Witch World by Andre Norton (1968)

Kaththea’s lamentable propensity for calamity and kidnapping strikes again. Swept away by an avalanche, Kaththea is captured by Vupsall nomads. Their Wise Woman Utta has need of one such as Kaththea. Old Utta will soon die. Kaththea’s magic potential make her a suitable Wise Women candidate. Kaththea yearns to escape. There is an obvious ally to help her flee. Alas, Kaththea is painfully aware that her primary talent may be trusting the wrong men…

In Kaththea’s defense, the bad decisions she makes in this book pale against the ones she made in the previous book, Warlock of the Witch World. At least in this one, she has not fallen for a hunky Lord of Pure Evil. She does learn!1 And the fact that her magic was temporarily locked away due to the events in the previous book facilitates many exciting adventures in this volume.

The Castle of Dark by Tanith Lee (1978)

Raised in the Castle of Dark by two ancient hags, Lilune sleeps by day and wakes at night. Her meals are a mysterious dark liquid. These facts are peculiar… but to Lilune they are just same old, same old. Boring. So she casts a simple spell that will enchant traveling harpist Lir into rescuing her from the Castle of Dark.

There are many heedless fantasy protagonists I could mention who would rescue a woman without paying much attention to such peculiar qualities as aversion to sunlight, death-like daytime sleep, or odd dietary needs—protagonists such as Northwest Smith—but Lir at least has an excuse, having been bewitched by Lilune.

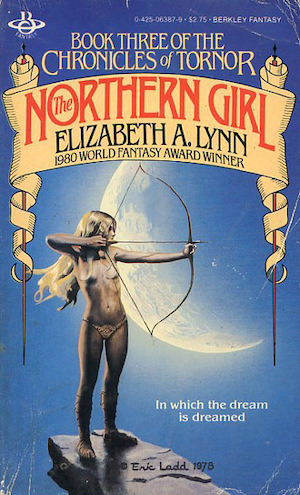

The Northern Girl by Elizabeth A. Lynn (1980)

Bondservant to powerful Arre Med, seventeen-year-old Sorren might well have spent her entire life in contented servitude to her comparatively benign mistress. Fate (and the schemes of Arre’s younger brother2) dictate otherwise. Sorren will leave her familiar world behind to find her proper role far from the only city she knows.

The Northern Girl has a number of stock plot elements, such as an orphan girl with special powers, political machinations, and so on, none of which head in the direction readers may expect. Lynn had a very clear idea where she wanted this coming-of-age story to end and she did not let herself get distracted from her goal.

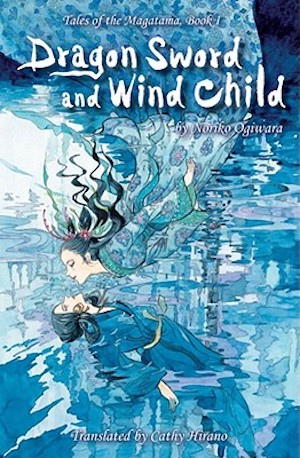

Dragon Sword and Wind Child by Noriko Ogiwara, translated by Cathy Hirano (1988)

Demigod Prince Tsukishiro resolves that orphan Saya, whom he has just met and about whom he knows nothing, must be his handmaiden. It’s a fairytale romance…a very dark one. In every one of Saya’s incarnations, she has met the Prince. In all of Saya’s incarnations, she perished almost immediately. Nevertheless, the former Water Maiden Sayura (of whom Saya is just the latest version) has a grand plan in which the current incarnation must play a role… even if reincarnation-induced amnesia means that Saya has no idea what the plan was, or what her role was to be.

Dragon Sword and Wind Child is part of a trilogy, Tales of the Magatama. Dragon Sword and Wind Child functions as a standalone fantasy novel. This is fortunate for Anglophone readers because while the second volume, Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince, has been translated into English, as far as I know the third one was not.

These are merely the first five works that came to mind. No doubt there are hundreds that I could have mentioned. Feel free to correct my lapses in the comment section below.

- More than one can say of Jane Gaskell’s Cija.

- How significant is the younger brother to the main plotlines in The Northern Girl? You will notice I never mention his name…

tap tap is this on?

I think we could give William Morris a nod too.

Given the topic is explicitly female authors as noted in the first paragraph, I’m going to say no.

The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia McKillip, full stop. I would have loved the book for the magical creatures alone, I was reading with full-on hearteyes after the first chapter for Sybel and Coren and learning to love after years spent avoiding all emotional entanglements…

I had a patron stop by the Information Desk at the public library t’other day, just to share with me “Y’know, I am absolutely the target audience for this “Romantasy” category. I love these kinds of books. But I hate hate HATE the name “Romantasy”. It sounds stupid. It sounds like they think that *I* am stupid. It sounds like crappy overpriced yoga pants. I hate it so much that I refuse to read anything with that label.”

To which I responded “… you’re not alone.”

It’s a true fact that women have been writing fantasy since the beginning. It’s also a true fact that cynical marketing departments have recently promoted the obnoxious portmanteau romantasy as a supposed genre. Any connection between those two facts is very tenuous from a literary standpoint and mainly aspirational from the standpoint of said marketing functionaries. I refuse to consider anything by the brilliant C. L. Moore as romantasy; and much as I loved Andre Norton novels during my youth, her attempts at writing anything with a strong romance element were ponderous and uninspiring.

Maybe after a few years of this romantasy business, the marketers will relent and give us Classic Romance, a la Classic Coke.

I would draw a distinction between Fantasy that has Romance, and Romance that has Fantasy. The latter case has the romance at the forefront of the story, and follows Romance genre traditions (like the happily ever after). The former encompasses quite a lot of traditional fantasy, and consists of fantasy novels that have a significant romance as part of the plot. I would bet money that of the latter, the ones written by women are more likely to be classed as romantasy. I have trouble picturing *anything* by Andre Norton under the romance label. Even in books where the characters pair up at the end, it’s extremely chaste and decidedly perfunctory.

I think there’s a lot of confusion when the two genres overlap. Romance fans will read books like the ones in this list, and wonder where the romance was. Fantasy fans will read a lot of the newer Romantasy books and complain about the shoddy world building and unsatisfying plots.

Oh yes. I picked up The Only Purple House in Town (by Aguirre, who I thought had enough experience to do more than put a couple of tweaks on the standard romance plot) and regretted it; after the Nth pass through “he/she can’t possibly feel about me the way I feel about him/her” I’d have thrown the book across the room if it hadn’t been borrowed.

Can I edit this? There used to be paranormal romance. Surely there still is. Apparently an actual difference of romantasy is that there’s more sexual intercourse, and sooner. The target audience wants to know. (And, take note, not all of James’s choices live up to this.) And yet even that isn’t new. At one time, very erotic writing was published as speculative fiction because opponents of very erotic writing weren’t reading speculative fiction, so there was a fair chance to get away with it.

And I recently mentioned scientifiction, but there must be something worse – I mean an undeservedly worse name. I think there was some resistance to “sci-fi”. And some strongly felt dislike, right or wrong, of SyFy.

Huh, apparently I have been giving wrong recommendations. I had interpreted “paranormal romance” as ” takes place in our world, partaking of romance tropes, and involving vampires, werewolves, etc.” and “romantasy” as “secondary world fantasy that uses romance-genre tropes”

Well, I may be misreading it too – as a word. I heard an author on BBC radio, in show “Open Book”, explaining vividly that when she writes it, it means sexytimes, and maybe that’s just what romance writing is in 2024. Other commentators from outside the speculative fiction field seem to struggle with a definition of “fantasy” as requiring a secondary world, forgetting “Dracula” obviously.

I’d say that secondary-world is “high fantasy”, stories on Earth are “low fantasy”, and then of course there’s “portal fantasy” where Earth people visit a secondary world. But some people take “high fantasy” as being where the fate of the world is at stake, politically at least, and “low fantasy” is low stakes adventuring. However, the first two published Discworld novels and the first two Middle-Earth stories of Tolkien show that low stakes can turn into high stakes rather quickly. This isn’t to say that these aren’t distinguishable types of story.

Some of the contradictory meanings polled by M. K. Lobb writing online in “Writer’s Digest” are also confidently asserted elsewhere:

“Romantasy is when the romantic and fantasy aspects of the story are equally important”

‘Romantasy is just a romance book with a fantasy world as a backdrop”

“Romantasy is when the plot would fall apart without the romance”

“Romantasy is a fantasy plot with a central romance that follows romance book ‘beats’, see: Romancing the Beat, by Gwen Hayes”

“Romantasy is just fantasy with ‘spicy’ scenes”

Another contradiction is claims I’ve just seen that romantasy characters have diversity / are overwhelmingly white, though I suppose you can be white and also diverse.

I want to argue against “the plot would fall apart without the romance”, but that’s reasonably a thing, that maybe when romance isn’t happening then wise characters will simply walk out of the book and leave the sex goblins to their own affairs. On the other hand, Harry Dresden for instance gets into trouble because people he cares about are in trouble with the story not necessarily being romantasy or sex goblin fantasy, although as I reflect, it very often is that with Harry.

Arguably a distinct type of literature is fantasy where the reader’s interest in it depends largely on appreciation of the romance content. Or of the sex content, which I’m still inclining to for the new word, because I believe we have other names for the other categories. Stories where if the romance or the sex is not portrayed credibly and engagingly, then the story is much duller – or much shorter. Or both.

If you rewrote “The Lord of the Rings” to include all the characters’ romantic feelings for each other, and explorations of those, wouldn’t the book need to be a lot longer? And, yes, they are nearly all male, so? I’m sure it’s been done anyway in fan fiction but probably not for the whole text. And not by or for me.

If it does mean sexy fantasy, that is not a new thing, but something to call it that doesn’t upset your parents or coworkers may be worth having.

Some of the opposition to “sci-fi” was sparked by the story (maybe true, maybe not) that a CBS executive told Gene Roddenberry “We don’t need another sci-fi show; we’ve got Lost in Space.”, causing readers to feel the term was used by people who didn’t understand the difference between LiS and OST.

Katherine Kurtz: the Deryni series – started in 1970 and consisting of five trilogies and a stand-alone novel. Last one released in 2014.

But Kurtz’s books aren’t romantasy, for the most part; they are straight-up fantasy. There may be a subsidiary romance in a few of them, but it’s never the central plot, or even equal to the non-romance plot. The possible exception is King Kelson’s Bride.

Also some ancillary material: Deryni Magic (mostly essays, if I recall correctly), The Deryni Archives (short stories), and Codex Derynianus (an encyclopedia).

I was going to pop in and say I thought there had been a more recent one… except I was thinking of Kerr’s Deverry, not Kurtz’s Deryni.

When I was in high school in the 80’s I read a lot of romance and fantasy so when I found something that combined the two I was thrilled. My mom was a huge fan of Taylor Caldwell but most of her stuff was not interesting to me until I stumbled upon The Romance of Atlantis. Later on I worked at Waldenbooks in the 90’s and time-travel and fantasy romance was really taking off and I read a lot of it. The new term “romantasy” does make me kind of giggle but in some ways I appreciate it’s rise.

The Dragon Prince and Dragon Star trilogies by Melanie Rawn was probably the first time I encountered something like Romantasy. Also another big thumbs up for anything written by Patricia McKillip already mentioned which I discovered a little later.

Anne McCaffery’s Pern novels. The Return of the King.

The Hero and the Crown & The Blue Sword by Robin McKinley.

My absolute favorite! But if Romantasy implies adult material, these would not qualify, they’re totally PG…

“The Northern Girl” is the last book in a trilogy- “The Chronicles of Tornor.” The first and second are “Watchtower” and “The Dancers of Arun.” Lynn wrote male romantasy as well as female, and the books cover a few generations in which tenets of sexuality, masculinity, self defense, dance and magic evolve. “The Northern Girl” calls back to “Watchtower” in subtle ways. I cherish my battered paperbacks.

If it weren’t labelled as SF rather than fantasy, I’d really have to go with _Fire Dancer_ by Ann Maxwell.

Oh lord, that thing. It kept getting a lot of recommendations on rec.arts.sf.written so I got the books when it was re-released, IIRC. I’m not sure I made it through all 3 books as I got tired of the wash-and-repeat plot of let’s-drop-off-another-lost-soul / Rheba’s obliviousness / Kirtn’s I-must-not-reveal-my-all-consuming-love-because-she’s-just-not-ready-yet. I enjoyed her Fiddler and Fiora mysteries (with her husband and writing as A.E. Maxwell) a heck of a lot more.

I’ve only read one, so I may have missed the lather/rinse/repeat of the sequels.

The Alaric novels by Phyllis Eisenstein, starting with Born to Exile (1978)

Every time I hear/read the term “Romantasy”, I immediately think back to Howl’s Moving Castle. Which is a book that FLEW so that Legends & Lattes (an alright yet boring book) and The House in the Cerulean Sea (a solid, beautiful entry into all of fantasy) could soar undaunted.

While I somewhat loathe the tag “Romantasy”, it is only because it is a basic publishing repackaging of all the basic concepts that we once referred to as “paranormal romance” or “supernatural fiction”. Romantasy, as this post establishes, isn’t anything remotely new.

And, yes, the term should fade as swiftly as it arose. The books, I suspect, shall endure. As they’ve done before, and as they should.

Long out of print, but: Joyce Ballou Gregorian’s “Castledown” trilogy.

The real difference between these classics, which have some romance, and “romantasy” by authors like Sarah J. Mass and Rebecca Yarros is sex. And the difference between “romantasy” (ugh the word is awful) and paranormal romance (which also includes plenty of sex) is that romantasy has stronger workd-building and stakes. So, yes, the word is awful, but it does signify something different. So glad to see these new adult women authors who cut their teeth on classic fantasy and who are now writing the stories they want to see with bad ass heroines and good magic systems, but with lots of sex. I’m totally here for it. I grew up with and love Patricia McKillip, Anne McCaffrey, Andre Norton, Esther M. Friesner, and Jennifer Roberson, but those stories don’t quite scratch the same itch as a smutty high fantasy that doesn’t fade to black.

Now wondering if Mists of Avalon would count; behold, there is sex in that, also romance, but less so on Happily Ever After.

I was too late to Mists of Avalon, didn’t get a chance to read it before the crazy child abuse info came out and now I can’t make myself do it without feeling squicky, alas.

Who is Happily Ever After by? On searching, I can only find the companion novel to The Selection series, which is modern YA.

Don’t forget the Sharing Knife books by Lois McMaster Bujold. Although many of her science fiction novels have present to strong romance elements, that series was written with the specific intent of having the romance as the main plotline. There are also the ever-delightful Penric books, a particularly tender and wonderful ongoing romance.

When I think older romantasy, I immediately think of Kushiel’s Dart by Jacqueline Carey.